Anyone who has spent a humid summer evening fending off mosquitoes or a hot summer day nursing mosquito bites will concur: Mosquitoes are a nuisance. Nevertheless, it’s the smells emanating from humans that predominantly allure these pests towards us.

In a scientific article released on Friday, researchers identified specific chemicals in human body odor that appeal to these insects. They did so by constructing a testing arena as vast as an ice rink, where they introduced the unique scents of different individuals.

Mosquitoes belong to the fly family and primarily feed on nectar. However, female mosquitoes, gearing up to lay eggs, require an extra protein-rich meal: blood.

At the very least, a mosquito bite results in an itchy red welt. However, such bites often escalate to life-threatening conditions, owing to the parasites and viruses these insects carry. One of the deadliest diseases transmitted by mosquitoes is malaria.

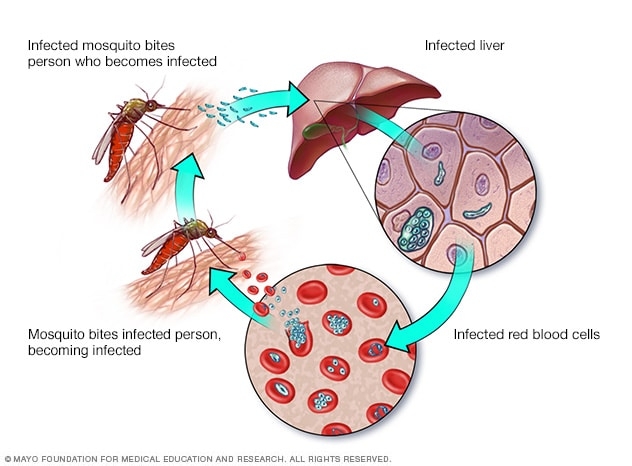

Malaria, a disease propagated through the bloodstream, is caused by minute parasites that inhabit red blood cells. When a mosquito bites a person infected with malaria, it ingests the parasite along with the blood. The parasite, after maturing in the mosquito’s stomach, “will migrate to the salivary glands and then be spat back out into the skin of another human host when the mosquito blood-feeds again,” explained Dr. Conor McMeniman, an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute in Baltimore.

Despite malaria’s eradication in the United States over the past century due to window screens, air conditioning, and upgraded drainage systems that thwart the growth of mosquito larvae, the disease continues to pose a threat worldwide.

“Malaria still results in more than 600,000 fatalities per year, primarily among children under the age of 5 years, and pregnant women,” said McMeniman, the chief author of the new study, published in the journal Current Biology. “It causes substantial suffering globally, and part of the motivation for this study was to comprehend how mosquitoes that spread malaria locate humans.”

McMeniman, along with Bloomberg postdoctoral researchers Drs. Diego Giraldo and Stephanie Rankin-Turner, the study’s lead authors, focused on Anopheles gambiae, a mosquito species prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa. They collaborated with Zambia’s Macha Research Trust, under the supervision of scientific director Dr. Edgar Simulundu.

The team was driven to develop a system that would enable the study of the African malaria mosquito’s behavior in a habitat reminiscent of its natural environment in Africa, McMeniman mentioned. They sought to compare the mosquitoes’ olfactory preferences across diverse humans, observe their ability to track scents over distances of 20 meters (66 feet), and study their activity during their most active period between 10 p.m. and 2 a.m.

To satisfy these requirements, the team constructed a facility as large as a skating rink, surrounded by six screened tents where study participants slept. Air from these tents, carrying the distinct breath and body odor of the participants, was channeled through long tubes into the main facility onto absorbent pads, warmed and laced with carbon dioxide to simulate a sleeping human.

The main 20-by-20-meter facility housed hundreds of mosquitoes that were treated to a buffet of the sleeping subjects’ scents. Infrared cameras monitored the mosquitoes’ movements towards the different scent samples. (The mosquitoes involved in the study were not infected with malaria, and they couldn’t reach the sleeping humans.)

The researchers discovered, much like picnic-goers, that some people tend to attract more mosquitoes than others. Furthermore, they identified the specific odor-causing compounds that appealed to or repelled the mosquitoes.

The mosquitoes were primarily drawn to airborne carboxylic acids, including butyric acid, a compound found in “stinky” cheeses like Limburger. These carboxylic acids, produced by bacteria on human skin, are usually undetectable to us.

However, another chemical called eucalyptol, found in plants, seemed to deter the insects. The researchers hypothesized that a sample with a high eucalyptol concentration might be attributed to one participant’s diet.

Simulundu expressed excitement at the correlation discovered between the chemicals present in different people’s body odor and the mosquitoes’ attraction to these scents.

“This discovery paves the way for developing lures or repellents that can be used in traps to disrupt the host-seeking behavior of mosquitoes, thereby controlling malaria vectors in regions where the disease is endemic,” said Simulundu, a coauthor of the study.

Dr. Leslie Vosshall, a neurobiologist and vice president and chief scientific officer of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, who was not associated with the study, shared a similar sentiment. “I think it’s a super exciting study,” she said. “It’s the first time that an experiment of this type has been conducted at this scale outside the lab.”

Vosshall’s research involves another mosquito species that transmits dengue fever, Zika, and Chikungunya. In a study published last year in the journal Cell, she and her team found that this mosquito species also seeks out the scent of carboxylic acids produced by bacteria on human skin. The fact that these two different species respond to similar chemical cues could potentially simplify the creation of mosquito repellents or traps.

This research may not immediately affect how to prevent bug bites at your next barbecue. (Vosshall mentioned that even washing with unscented soap doesn’t eliminate the natural scents that attract mosquitoes.) However, she pointed out that the new study “provides us with some valuable insights into what mosquitoes use to hunt us, which is crucial for us to plan the next steps.”

©world-news.biz